The Place Where the Streams Came Together

A few years ago, on October 6, 2004, to be exact, at an amazingly opportune change point in my work at the University of Louisiana—at the coincidence of a confluence of seemingly unrelated streams of events involving multiple persons, organizations, and agencies that only God Almighty could have brought together at just that particular time and place—I received an open invitation to submit a proposal for a book or manuscript from Dr. Sadanand Singh, Chairman of the Board and CEO for Plural Publishing: International Publishers for the Health Professions. Sadanand had signed the letter along with his wife, Dr. Angie Singh, President of Plural Publishing.

Back then, I had no idea about the incredible story of the life of Dr. Sadanand Singh, the courageous entrepreneur, scholar, and philanthropist, who had extended the invitation. I knew him from my years as Head of the Department of Communication Disorders at UL Lafayette and as the founder of a couple of other companies including Singular Publishing which all of his colleagues understood as a play on his name. Later, he would multiply the linguistic fun by calling his next publishing company, “Plural.”

I remember him greeting me at our first meeting with a warm handshake on a sunny day in Palm Springs, California, in the spring of 1998. I was there as a representative of my university and department for the national meeting of the Council on Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders. Dr. Singh had arranged for one of those delicious mid-afternoon out-of-doors snack receptions—the kind where conference participants love to have a cool drink and finger foods while visiting with colleagues and friends. (Also, they can fill up and avoid paying for a more expensive meal somewhere else a little later on. :))

From the moment I first met him I felt as if I had known him all my life. He shook my hand in his right hand and put the left hand on my shoulder as if we were family. He had the warmth of kindness in his touch and the welcome light in his eyes. It was impossible not to feel the love inside the man.

Years later, after his departure from this life (just last spring), I would learn about his world before he founded Singular Publishing in 1990. He actually died on February 27, 2010, but I only learned of his death a couple of months afterward at the Starbucks on the River Walk in San Antonio, Texas, just diagonally across the river from the central Hyatt Regency that gives out onto the River Walk.

Dr. Stephen D. Oller wrote an email to say that he had just learned of Sadanand Singh’s death. I immediately did a search and began to learn about Sadanand’s life before I met him and before he became one of my most valued allies in the quest to get to the bottom of the autism epidemic. It was because of my work with Dr. Singh that my coauthors and I would connect up with Dr. Robert J. Titzer and his discovery that will, I believe, be of great interest to many families struggling with one or more cases of “nonverbal” autism.

But, before I get to that, I need to fill in a background scene that gives depth to the whole story and connects it with the posts preceding this one in a way that will, as they say, cause chills along the spines of my readers.

A Lifetime Before the One I Knew

Only after learning of Sadanand’s death did I find out about the lifetime before I ever knew him. I learned of a former wife, audiologist, Kala Singh, who died in the September 5, 1986 attempted hijacking of Pan Am Flight 73. The plane had been taken over by 4 members of the Abu Nidal Terrorist Organization in Karachi, Pakistan. It was a Boeing 747 en route to New York with a routine stop-over in Karachi. She, Dr. Sadanand Singh and their children, along with a grand total of 360 passengers were on board.

The terrorists were dressed as Karachi Airport security guards armed with assault rifles and pistols. It was learned later that they also carried belts loaded with grenades and plastic explosives. After boarding the plane and taking over, they were joined by a 5th terrorist, Zayd Safarini, who began to collect passports looking for Americans.

Safarini’s first victim was a 29-year-old Indian named Rajesh Kumar, a recently naturalized citizen of the U. S. A., who was headed back to his home in California. Safarini marched Kumar to the front of the plane, forced him to kneel with hands on top of his head, and then after 15 minutes of failed negotiations with authorities shot Kumar in the back of the head in front of many of the passengers. Meantime, while commandos awaiting an order to storm the plane also observed from a distance, Zayd Safarini shoved Kumar through the front door of the Boeing 747 aircraft where the fatally injured man fell to the tarmac about 30 feet below.

The ordeal climaxed 17 hours later when the frustrated terrorists opened fire on the 360 passengers. Moments later the Pakistani authorities ordered the commandos to storm the plane. Sadanand and 2 of his 5 children were injured in the shoot-out and his wife, Kayla at the age of 36 years, was among the 13 passengers and 9 other persons killed in the melee.

The Man I Knew

Before learning about his former life, based on our working relationship as author to publisher, I saw Sadanand Singh as a man of courage, depth, and intelligence. After learning of his former life, to think that he could have picked himself up after such the traumatic events of September 5, 1986, gave me a whole new appreciation for who he was. He had already won my admiration for his courage in permitting and even supporting my pursuit of a way to halt the evident autism epidemic, but knowing about what he had been through himself with the loss of Kayla as well as injuries inflicted on himself and two of his children put everything I knew of him in a different light.

In the course of our work in the author/publisher relationship, I learned that Dr. Singh himself had been approached by special interest groups, who it seemed had the intention of quashing our projects. I am quite certain this happened more than once. It seemed plain enough that they tried to persuade him to put a stop to our ongoing research, and to finished original work which he had already committed to publish.

In my judgment, they underestimated Singh. But in his wisdom, taking note of all the angles, Singh nurtured each of the book projects we did under his direction until he, and his team of editorial peer-review experts, were convinced the book in question was ready for the marketplace and could withstand the heat of professional scrutiny. He wanted gem stones and gold at the end of the examination in the crucible.

Also, as folks following the public dialogs about the autism epidemic know very well, you don’t have to be, as they say, a rocket scientist to imagine the opposition falling on any publisher in the health sciences who may dare to publish findings that clearly implicate power-brokers with looming liabilities. I know that Singh could not have known anymore than we did where our work would eventually lead, but it was clear enough at the outset that we were venturing into deep and shark-infested waters.

The Streams Ran Together

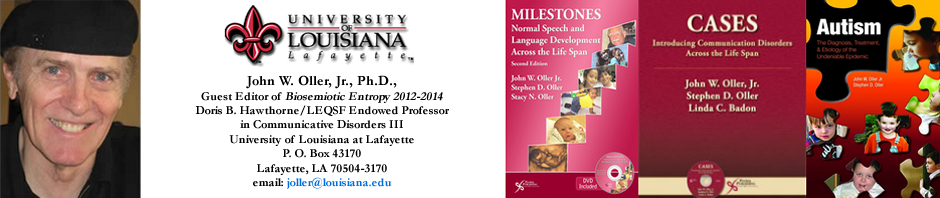

Nevertheless, in my judgment it was only by the grace of God, at such a time and such a place with the best of motives, determination, and a lot of genuine “positive energy” to quote Dr. Singh, that we joined hands. With Singh’s knowledge and full approval I recruited my coauthors Dr. Stephen D. Oller (then still a graduate student at UL Lafayette) and Dr. Linda Cain Badon, CCC-SLP (also a mentor and dissertation committee member for Steve) and the three of us submitted two book proposals.

Dr. Stephen David Oller, now on the faculty of the Department of Biological and Health Sciences at Texas A&M University (Kingsville), actually completed his dissertation in the very PhD Program which I came to the University of Louisiana to build. Interestingly, after 4 years worth of work and the winning of a perpetual grant from the Board of Regents and then Governor Mike Foster (one that has netted $800,000 at the time of this writing) in 1999, the Applied Language and Speech Sciences PhD Program was finally approved by the Louisiana Board of Regents in the summer of 2001. That same summer, Stephen D. Oller announced his independent (and complete surprise) decision to give up a full fellowship in the Cognitive Sciences PhD Program at UL Lafayette, in order, as he put it, “To support the home team” and to focus his attentions on the theory and research that most interested him.

Flashing ahead from the founding of the PhD program in 2001 to the spring of 2005, I will never forget the first telephone conversation with Sadanand. That day on the phone, Singh said he knew who I was, promised to treat me exactly as he would his “best-selling authors” among whom he mentioned Dr. Ray Kent. After being assured that Sadanand had not mistaken me for my famous brother D. Kimbrough Oller, whom he also knew well both by reputation and personally, Singh assured me that he knew me and my work and that he was very interested in seeing the proposals I had in mind. I will never forget his concluding words. He said, “John?” and then he paused until I confirmed that I was listening, and then he said, “Let’s keep the positive energy flowing between us.”

An Unexpected Discovery

Long before we began writing Milestones: Normal Speech and Language Development Across the Life Span which would appear under the Plural Publishing imprint in 2006, we realized that babies at a very early age were taking interest in printed words and the processes associated with literacy. Other researchers had observed that babies are often fascinated with books, more sometimes than their toys, well before they are able to say their first intelligible word. A couple of my own doctoral students at the time (ones whose dissertations I was chairing and in which Dr. Badon was also involved as a committee member), commented that their baby, from well before 10 months of age, would sit and turn the pages of a book as if reading it. (Both of those individuals, Dr. Liang Chen and Dr. Ning Pan, finished up their graduate work in 2005 and Dr. Chen joined the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of Georgia.)

Why did babies seem so interested in print? Was the apparent interest just an unexplainable infant curiosity? Was the seeming interest only imitative behavior as some had supposed? Was the baby merely copying what he or she had seen the parents doing? Or was there something more going on?

One day early in the course of our work, I was talking with Dr. Badon about early language and literacy when she pointed to two bits of knowledge that would shape the entire Milestones project, and the Cases book to boot. First, she directed attention to the 4-D ultra-sound technology developed at Create Health Clinic in London by Dr. Stuart Campbell. His moving video images of babies in the womb, according to our reasoning in both the Milestones and Cases books, ought to (and we believe eventually will) vaporize the silly “gas theory” of infant smiling. (Though in 2010, there are still vestiges and hangers on to a theory that never did make sense!)

That false theory does serve another useful purpose however: It does show that ordinary people ought to ask reasonable questions of medical doctors and not to naively accept what they say. Doctors can be completely wrong and the gas theory shows that a majority of those trained in pediatrics and obstetrics are not thinking things through from a logical perspective. This lesson is especially important when it comes to the autism epidemic. Doctors with the MD and plenty of alphabet soup behind their names can be incredibly naive when it comes to thinking things through and many, as Brian Jepson, MD, has noted, do not read the research! But they ought to…

Dr. Campbell’s application of 4D Ultrasound has already helped to change the way human babies are thought of and the way students of human development see themselves. Human babies never do go through a fetal larva stage, or tadpole stage as naive evolutionists once claimed. Human babies have distinctly human DNA from conception and they do all kinds of things in the womb that were supposed to be impossible until weeks or even months after birth, like displaying a perfect social smile—a sign that Dr. Campbell agreed in my first conversation with him shows security and contentment, not stomach gas… In fact, our research shows that all the milestones keep getting shoved farther and farther back into the baby’s earlier and earlier experience, even before birth.

The second key bit of information about ongoing work that Dr. Badon pointed all of us to initially was the work of Dr. Robert J. Titzer. When we first got in touch with him to ask to use his documentary evidence of babies reading before they can talk, his willingness to share everything he had was heart-warming and inspiring. Before any of the really fancy infomercials hit the market, Dr. Titzer gave us permission to put his video clips on our DVD for Milestones and would later extend the same privilege to us for both of the other books pictured above, Cases and Autism.

What Dr. Titzer demonstrated was predictable, at least after the fact, by the theory of abstraction. That theory is explained in detail in the Milestones book. Dr. Titzer’s finding not only moves the age of reading readiness back to the time prior to the child’s first intelligible spoken word, but the theory of abstraction explains how the baby is able to achieve the pragmatic mapping of an abstract sign onto a particular object, e.g., the word “Mama” onto the person who responds to that name, at such an early age.

The principle illustrated in Dr. Titzer’s methods of teaching reading is simple: As soon as a baby, or anyone, is able to understand the meaning of a word or phrase, they have already reached a point in development where they will be able to read the same word or phrase presented in a printed form. In fact, as Aleka Titzer demonstrated at 9 months of age (with her dad’s help) she was able to learn to read lots of words, “bucketloads!” as my youngest grandson Brenden would say, before she could say them out loud. Even after viewing the process, skeptical teachers, speech-language pathologists, reading specialists, psychologists, linguists, and so forth, all need a little time to think it all through.

After they do, the realization that babies really can read comes with a bang. One of my favorite testimonials, recorded by my friend Chad Murdoch, President of M2G Media, features a mom, Lindsey, who happens to be a, yep you guessed it! speech-language pathologist (or if not she sure talks just like one). You have to hear what she has to say. The genius behind Lindsey’s videographed interview is none other than Chad Murdoch, leader of the team at M2G Media. Chad’s company, and he himself, is largely responsible for the “grand slam home run” of an infomercial he has put together for the “Your Baby Can Read” series.

To draw the logical inference about the applicability of Dr. Titzer’s findings, and the implication of the theory of abstraction, for individuals with communication disorders, say, “nonverbal” autism, is not difficult. Also, there is growing evidence that even persons who appear to be hopelessly “nonverbal,” that is, persons who seem unable to speak and thus confined to a kind of imprisonment within their own skins, will, in many cases, be able with appropriate therapeutic intervention following the essential path mapped out by Dr. Titzer’s pioneering work, to become literate.

For an example of a person who became literate, I believe after the age of 11, having become “nonverbal” from before his second birthday. Dov was diagnosed with autism at about the age of 3 years after a regression at about 15 months. See the story of Dov Shestack’s bar mitzvah celebration and the speech he was able to write and present, as told at the end of the lecture by Dr. Tom Insel, Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, that I will link right here. Dov could not speak at his recent bar mitzvah but he was able to type out a speech with a keyboard.

A reasonable inference from all the foregoing is that many persons with what is thought of and referred to as “nonverbal” autism may be able to achieve a substantial level of communication through literacy.

logic